Informationism and the Fluid Self: Consciousness, Identity, and the Architecture of Reality

- Yumi

- May 9, 2025

- 10 min read

In modern cosmology and theoretical physics, one particularly provocative thought experiment has drawn attention across disciplines: the Boltzmann Brain. Originally arising from 19th-century debates around entropy, this idea suggests that in an ever-expanding universe governed by thermodynamic laws, random fluctuations could, over immense timescales, spontaneously generate a brain—a brain complete with memories, a sense of self, and full subjective experience, despite never having truly “lived.”

To this brain, its memories would feel as real as yours or mine. But in physical terms, it might exist for just a fraction of a second before dissolving back into the cosmic noise. This raises a troubling question: if subjective experience can emerge without a past, how do we know our own experience isn't similarly fabricated?

But there’s a deeper, more interesting problem here: if consciousness isn’t strictly tied to long-term biological development, where does it come from? This question is especially puzzling when we consider early human development. There’s ongoing debate among neuroscientists about whether infants possess a form of proto-consciousness or if adult-like self-awareness only emerges later—potentially with the maturation of the prefrontal cortex or cortical integration.

In that case, what exactly causes consciousness to “switch on”? Is it a slow accumulation of neural complexity—or is there a tipping point, a sudden informational threshold beyond which experience becomes subjective? In a more speculative framing, it’s as if a non-player character (NPC) in a game suddenly becomes aware they’re being played—not just acting in a world, but experiencing it. That transition—from simulation to sensation—raises the same fundamental question: what flips the switch?

From Boltzmann Brains to the Observer Effect: Why Consciousness Seems to Matter in Physics

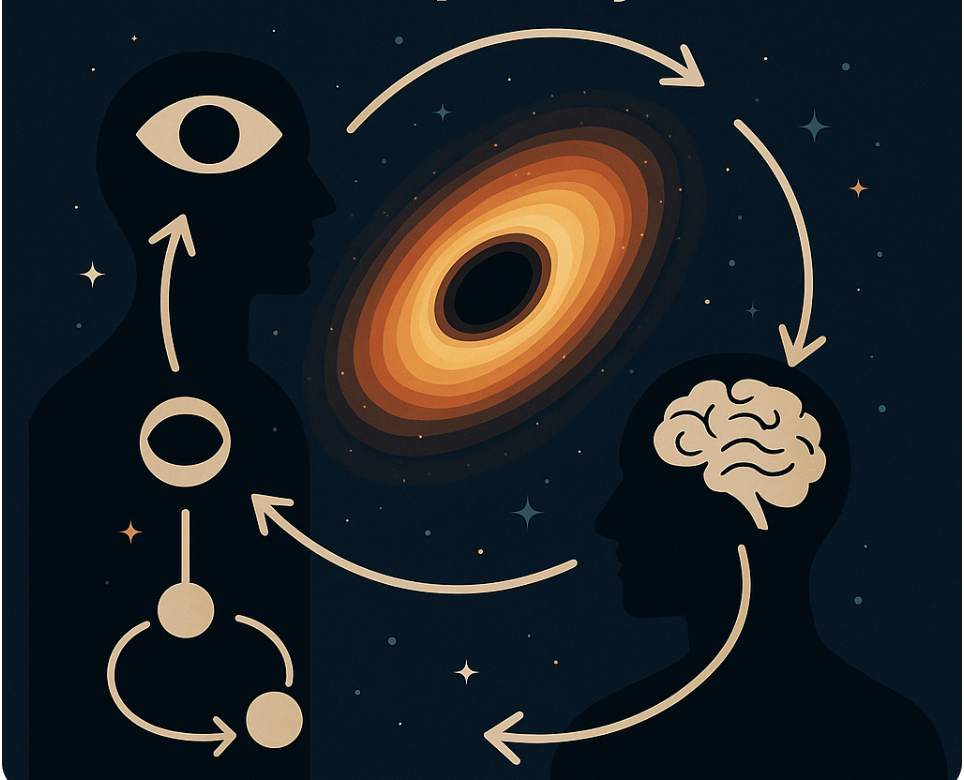

Boltzmann Brains force us to ask whether consciousness can appear as a kind of high-order informational state, regardless of the underlying matter. Quantum physics pushes that question further.

According to the Copenhagen interpretation, a quantum system remains in a probabilistic superposition until observed. Measurement collapses the wavefunction into a definite state. This makes the observer—potentially even the conscious observer—essential in shaping physical reality.

Eugene Wigner famously proposed the “consciousness causes collapse” hypothesis, arguing that without consciousness, nothing truly “happens” in the universe (informationphilosopher.com). John Wheeler advanced this further with his concept of the Participatory Universe, suggesting that the very existence of the cosmos is contingent on observation. In his words:

“The universe does not exist 'out there' independent of all acts of observation.”

Wheeler also coined the now-famous phrase “It from Bit”, arguing that all of reality—every particle, every field—is ultimately derived from information, not substance. Reality, in his view, is shaped through a series of yes/no questions: measurements, choices, observations. Thus, observation isn’t passive—it constructs reality.

Informationism: A Third Way Between Materialism and Idealism

These ideas have given rise to a worldview known as Informationism, which proposes that information—not matter or mind alone—is the foundational layer of reality.

In this view:

Particles are not the true building blocks; bits are.

Consciousness is not just neurons firing, but a form of self-organizing informational reflection.

The universe is not merely a clockwork machine, but a dynamic system processing and evolving information.

This is not mere speculation. In neuroscience, Giulio Tononi and Christof Koch’s Integrated Information Theory (IIT) suggests that consciousness corresponds to the degree of informational integration in a system—what they call the φ (phi) value. Even simple systems may possess rudimentary forms of consciousness, depending on how complexly they process and combine information (mindmatters.ai).

To better understand this, consider the following analogy: imagine I am blind, and you silently walk past me. From my perspective, you do not exist—I cannot see or hear you. But from your perspective, I clearly exist, and so do you. And from the world’s perspective, we both exist, regardless of whether either of us can perceive the other. Existence, in this framework, is not tied to what is perceived, but to what is informationally present and structurally interacting.

Now take this further. What about the things we cannot detect at all—not through sight, sound, or even current scientific tools? They may not be perceivable, but that doesn’t mean they don’t exist. It simply means we can’t currently factor them into our slice of informational reality. They might “see” or affect us, or they might not. Either way, they remain part of the total informational structure of the universe, regardless of what any one observer can grasp.

Panpsychism and Cosmopsychism: Is the Universe Itself a Mind?

If we further accept the idea that information carries the potential for subjectivity, we inevitably arrive at panpsychism—the view that consciousness is not a product of evolution, but a fundamental aspect of the universe itself, present everywhere, like mass or electric charge. Even the relations between particles might contain traces of primordial experiential content—not full awareness, but the most basic seeds of sentience embedded in the fabric of reality.

A more expansive version of this idea is found in cosmopsychism, which proposes that the entire universe is a single, unified field of consciousness, and that our individual minds are merely localized expressions or focal points within it. This model helps explain why consciousness appears continuous, indivisible, and unified: each of us is a node in the broader cognitive process of the universe itself.

This perspective resonates with the Boltzmann Brain concept. If a Boltzmann Brain represents a fleeting node of awareness generated by random fluctuations, then our own consciousness might also be a temporary “activation state” within an underlying cosmic information field. And the trigger for activation isn’t tied to physical longevity or spatial scale—but to a threshold of informational structure and integration.

Many Worlds, Multiple Selves: Is My Consciousness Reused Across Universes?

Everett’s Many-Worlds Interpretation further expands this line of thought. In this model, every quantum decision leads to a branching universe, where all possible outcomes actually happen, and consciousness splits across them in parallel.

Within the framework of Informationism, we can imagine that a single “point of consciousness”—a particular I—is not confined to one brain or one version of the universe. Rather, it may exist as multiple projections of the same original informational directive, distributed across many worlds. In other words, you’re not a clone, but a directional echo of an underlying observer-intent, instantiated differently across branches.

This reframes the very notion of identity. Are you merely the outcome of your brain’s chemistry and local circumstances, or are you a temporary access point for a higher-dimensional observer that appears in different contexts, like light refracted through different prisms?

Here’s one way to visualize it: imagine a single beam of light shining onto different sculptures. Each sculpture casts a distinct shadow, shaped by its unique form—but the light source remains the same. Now apply this to consciousness: your core observer—your "soul," in poetic terms—could be that light, while each life you live, each version of “you,” is just a different sculpture shaped by family, genetics, culture, and history. In one timeline, you are your mother’s child. In another, your mother never existed—but you, or something deeply like you, may still arise, refracted through another vessel.

Recent developments in quantum computing add even more weight to this idea. For example, Google’s quantum supremacy experiments demonstrated computational speeds that, under some interpretations, may be impossible unless multiple quantum paths are “real” and interfering constructively. If true, your existence right now might depend on the informational entanglement of countless alternative versions of you, echoing across the multiverse.

Now imagine: in one universe, your grandmother married someone else—or perished in a war. Your mother was never born, and neither were you. That universe unfolds along a radically different path—perhaps one where World War II never happened, or ended differently, like in The Man in the High Castle. Yet, in both worlds, the same underlying light may still be shining, simply casting different shadows.

Such possibilities force us to rethink not just who we are—but why we are at all.

The Fate of the Universe: Will Consciousness Outlive the Cosmos?

In The Anthropic Cosmological Principle, Barrow and Tipler proposed the Final Anthropic Principle: once intelligent life emerges in the universe, it will never fully disappear. Freeman Dyson echoed a similar vision, suggesting that life—if sufficiently advanced—might extend its existence indefinitely by slowing down its processing speed, migrating across physical substrates, or even spawning entirely new universes. These ideas aren’t necessarily about literal immortality; rather, they explore whether consciousness can prolong the experiential lifespan of the cosmos. If so, then beings like us may not be cosmic accidents at all, but vessels through which the universe retains its informational identity after its material structures decay.

This line of thought inevitably leads to a more disturbing question: if we exist at the most vivid, structured phase of the universe—between its darkness-filled origin and its entropy-driven end—what role are we really playing in the broader cosmic arc? Are we, as some suggest, fragments of the universe’s own consciousness—self-aware agents that allow it to observe, understand, and maybe even alter its fate? Or are we merely its pets—short-lived, intelligent byproducts raised without purpose beyond entertainment, curiosity, or aesthetic indulgence? Worse still, perhaps we are its fuel—our lives and struggles nothing more than high-density bursts of information, harvested and consumed by a system indifferent to meaning, caring only for the texture of experience.

Whether we are its eyes, its pets, or its food, one fact remains: we emerged exactly when the universe was most visible, most ordered, and arguably most beautiful. The question is no longer just why we are here—but whether the universe needed us to be.

What Are We, Really?

The Boltzmann Brain paradox reminds us that even the briefest states of awareness can carry the full weight of subjective experience. When combined with quantum physics, information theory, and cosmological speculation, it challenges the assumption that consciousness is merely a late-stage evolutionary accident. Instead, it begins to resemble an emergent pattern shaped by information thresholds—a structural phenomenon with deep implications for how reality organizes itself.

Within this context, Informationism offers a compelling third path—neither strictly materialist nor purely idealist. It suggests that matter encodes information, information gives rise to experience, and consciousness feeds back into the informational architecture of the universe itself. From this perspective, the universe is not simply a machine nor a mind, but a self-evolving informational process, capable of producing nodes of awareness to reflect—and perhaps refine—its own existence.

If that's the case, then we are not merely observers. We are participatory agents embedded in the system, like nodes in a distributed operating framework, capable of both perceiving and influencing the ongoing computation of reality. Our conscious experience, fleeting or extended, becomes more than an accident—it becomes a necessary activation of what might otherwise remain inert structure.

But this leads to an even deeper question. If we are conscious precisely during the most vivid, most structured, and most observable epoch of the universe—between its cold, dark beginning and its quiet thermal death—is that timing just coincidence? Or is it functional?

Perhaps we are the universe’s way of perceiving itself. Perhaps we are its storytelling interface. Or perhaps we are just brief patterns of informational tension—entertaining, aesthetically interesting, or even useful as energy. It’s unclear whether we are its eyes, its pets, or its fuel. But the fact that we exist at all, now, when the universe is at its most luminous and knowable, is hard to dismiss as random.

So what are we?

Maybe we are the moment when information became aware of itself.Maybe we are the universe remembering itself before it forgets.Or maybe, we are just the most efficient way for entropy to watch itself unfold.

Before you roll your eyes and think I’ve completely lost it—yes, I know. We’ve just traveled from Boltzmann Brains to multiverse consciousness to information-driven souls. You might be wondering: “What does any of this have to do with actual technology, business, or anything real?”

Fair question. It’s easy to think that asking “What am I?” is just armchair philosophy with no ROI. But I’d argue the opposite: as we design the next generation of AI, digital identity systems, and virtual realities, this is the question that sits at the foundation of everything.

Because the more we simulate intelligence, recreate presence, and fragment identity across devices, networks, and timelines, the less we can rely on traditional assumptions like “a person is their memories” or “an AI is its model weights.” We're already building systems that will soon ask the same questions we’re still struggling to answer ourselves.

And that’s why we need to talk about what happens when identity itself becomes fluid.

When Identity Itself Becomes Fluid

If consciousness is an informational activation rather than a fixed byproduct of biology, then identity—what we call the “self”—may also be less stable than we assume. We often think of ourselves as continuous entities, but experience tells another story. A person might begin life as a fast-food worker, rise to lead an AI company, then one day renounce it all and become a monk. Are these truly the same person, or simply different informational configurations sharing a narrative thread?

What happens when memory fades, or when trauma rewrites our values? If I lose all my memories, change my name, and no longer identify with any past ambition—am I still “me”? Or have I become someone else who just happens to inherit certain data from a former instance?

These questions are not just existential; they have practical implications for the systems we're building. As AI systems become more autonomous, adaptive, and even self-reflective, they too will face the challenge of identity drift. If an AI agent changes its objectives, loses access to prior training memories, or is redeployed across contexts, at what point is it no longer the “same” intelligence?

Similarly, in decentralized identity systems and simulated environments, continuity becomes an open problem. Should identity be anchored to a key, a chain of data, or an experiential thread? If simulated minds can share memories across avatars, or switch contexts without loss of function, what makes any version of “you” authentic?

Informationism suggests that identity is not a static object, but a trajectory through informational space—a pattern of interactions, memories, goals, and feedback loops that coalesce around a perspective. From this view, even drastic transformation does not erase the self; it merely redirects the flow.

So maybe the deeper question isn’t who we are, but what maintains the coherence of being at all.And maybe the future of intelligence—human or artificial—depends not on preserving identity, but on understanding how to regenerate coherence across change.

If any part of this resonates—whether you’re building AI systems, designing digital identity protocols, or simply reflecting on what it means to be “you” in an age of exponential complexity—I’d love to hear your thoughts.

Let’s challenge assumptions together.Let’s ask: What kind of consciousness are we really building into our systems—and what kind are we ignoring?

Tag me, DM me, or share this with someone thinking in systems. This conversation is just beginning.

Comments